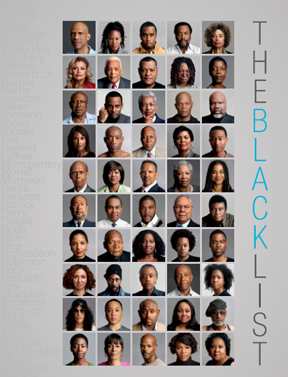

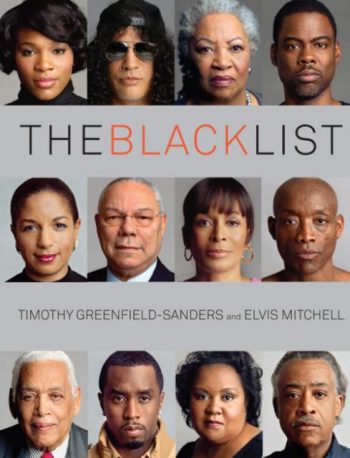

The Black List 50

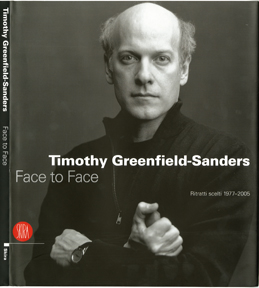

The Black List: Portraits by Timothy Greenfield-Sanders

Published by LCP, San Diego, CA. 2011, 110 Pages

Introduction by Martin Sullivan, Portraits by Timothy Greenfield-Sanders

On display in the National Portrait Gallery is a remarkable nineteenth-century painting by Christian Schussele called Men of Progress. Completed in 1862, it depicts nineteen inventors and scientists who had much to do with America’s triumphs during the Industrial Revolution. As the title suggests, all the sitters are indeed male, and not surprisingly for that era, all are white. Many of their names remain familiar today: Cyrus McCormick (the mechanical reaper), Samuel Colt (the revolver), Elias Howe (the sewing machine). In a fictitious setting, the artist has portrayed them clustered around the painter/inventor Samuel F. B. Morse, who is seated with his telegraph machine. They are an impressive group. You might call them their era’s White List.

Timothy Greenfield-Sanders’s inspiring new exhibition, “The Black List,” is a fresh twenty-first century take on the same theme: a collective portrait of people who have had, and continue to have, a transformative influence in American life. The Smithsonian’s National Portrait Gallery is honored to present this project in the nation’s capital and to celebrate the individuals whose images are on view.

Timothy readily concedes that his subjects are not intended to represent a definitive Top 50 list of contemporary African Americans. Countless more could be included. But even a quick survey of these names and biographies confirms what a remarkable show it is, and what an impact this group has had.

“The Black List” has been installed in a magnificent room that adjoins our long-term exhibition entitled “Struggle for Justice.” This proximity is not accidental. “Struggle for Justice” highlights the epic personalities of the civil rights era and other American movements for inclusion and equality. Had it not been for the courageous leadership of individuals who personally struggled for justice, a twenty-first century Black List might well be shorter and narrower in scope, and the nation would be the poorer for it.

I take pride in the Portrait Gallery’s collaboration with our gifted friend Timothy Greenfield-Sanders, which has been ably spearheaded by Curator of Photographs Ann Shumard. We are all grateful to AT&T for its generous sponsorship of this exhibition. As a historian, I can’t help but note the linkage of our sponsor’s original full name, including the word “telegraph,” with the nineteenth-century inventor who was at the center of Men of Progress. Like Samuel F. B. Morse, who achieved acclaim as a portrait painter long before he revolutionized the technology of communication, many of the personalities featured in “The Black List” are individuals who have distinguished themselves in multiple ways. They have our admiration and gratitude.

Martin Sullivan, Director, National Portrait Gallery